Published Date: 05-10-17

By: Gregg LaGambina

Ninth in the series.

Of all of the things we take for granted about the movies and shows we love, surely the human voice has to be near the top of the list. We know people will talk, but how much do any of us think about why they are speaking the way they are speaking and who might have taught them how to speak that way? We might notice the special effects, the performances, the story’s twists and turns, but do we ever really think about the sound of an actor’s voice? Sure, if it’s Yoda, or Marlon Brando’s cotton-ball-chewing Godfather. But what about Alison Bailey, the lead character from Showtime’s The Affair?

We have an actress (Ruth Wilson) who was born in Kent, England and she’s playing a woman from Montauk, along the south shore of Long Island. Noah Solloway is played by Dominic West, also British, portraying a Pennsylvania-born New Yorker. This is when someone on The Affair calls dialect coach Kohli Calhoun. And if you think it’s her job to just “get rid of the British accents,” well, that’s one way you’re taking the work Calhoun does for granted.

She will describe her trips to Montauk, interviewing and recording lifelong residents, coming back home to study the sounds and inflections and phrases, and seeking vocal tics and colors and sounds she can use to help Wilson become “Alison Bailey of Montauk” for The Affair. She also will help a new actor find their performing voice, which is part of the work she’s done with Eve Hewson (The Knick) and Bella Heathcote (50 Shades Darker). She will tell you how she taught Damian Lewis (Homeland), another expat Brit, who plays a hedge-fund manager from Yonkers, New York – on Showtime’s Billions – yet another dialect of the metropolis with its very own sound.

Somewhere in the midst of all of this, Kohli Calhoun finds time to be a musician and a champion for creativity of all kinds. Speaking with her, you soon understand why some actors repeatedly request to work with her. Her own voice has a precise level of enthusiasm that never floods over into condescension. Talk to her about the weather and you will somehow come away feeling encouraged and more confident. This might be why after teaching stints at both New York University’s Tisch School for the Arts and the Stella Adler School of Acting, she was voted “Best NYC Dialect Coach” twice in a Backstage reader’s poll.

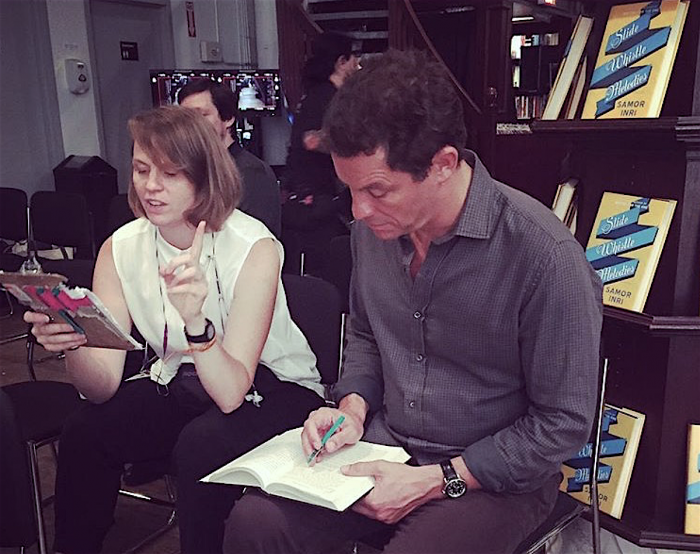

Recently, CreativeFuture visited with Kohli Calhoun to learn more about the human voice, how coaching dialect involves a lot more than just teaching someone how to do an impression (or lose an accent), and why she can find something to appreciate even when she watches a film and can hear every wrong note in a person’s voice, while the rest of us are on the edge of our seats for entirely different reasons.

Gregg LaGambina: What inspired you to become a dialect coach?

Kohli Calhoun: I’ve always just loved the sound of the human voice. I love the way people talk. I love different voices, different vocal qualities – this person has a high voice, this person has a raspy voice, this person has a lisp, or an accent, or a cold. And I always did theater when I was growing up and I just loved accents. I was totally that kid. Every play, community theater, drama program, camp – every single character, I thought, “You know? I think they should have an accent.” [Laughs]

I’d be like, “This person should be from France. This person should be cockney.” I didn’t know if any of it was appropriate to the material, it was just fun to do! Then, I went to drama school and I realized that I could actually make a living from this; and that I seem to be very skilled at it. I have incredibly sensitive ears.

When I was little, every time I would watch any show filmed in Canada – this is obviously pre-Netflix; we’re talking cable – and any time a show was from Canada, I would instantly know. If we watched something filmed overseas, I would figure out the accent and instantly be able to mimic it. I was really into it. In drama school, I started coaching people who were taking accent and dialect courses. I was really good at them and I loved those classes. I started coaching my friends in school. I’d be like, “I heard you have some scenes in ‘Our Town.’ Would you like a little help with that?” [Laughs] And, then, it just kept building and sort of came out of all of that.

GL: A lot of people who pursue work in the arts tend to start out in one place and end up doing something else, far removed from their original ambition. You sound as if you knew exactly what you wanted to do.

KC: It’s funny, right? My parents were both really into theater, so I always listened to those big Broadway and West End musicals and a lot of those cast recordings. People like Andrew Lloyd Webber – you’d have those librettos, so you’d hear so much story mixed in with the songs. I was really immersed. I saw every play that came to our town. I did all sorts of community theater. I was so immersed in all that stuff – storytelling and puppetry. I respected it, loved it, knew so much about it, was entranced by it, and then just felt like, “Ooh, I could be part of this someday!” When I was about 15, I saw some movie and there it was in the credits: Dialect Coach. I thought, “Ooh! That’s a thing?”

GL: What’s the difference between mimicking an accent, learning how to speak in a dialect, and just doing an impression of an accent? Is there a difference?

KC: Totally. That’s a super good question. An impression is a broad stroke that sits on top of an accent. I have a friend who is a fairly prominent standup comedian and she’ll hit me up for some things like that. I might listen to her for a while and then we work on it from there. We don’t dig into it and build it from the toes up, you know? Whereas, if we’re really doing a dialect for an actor doing a British accent, for example, versus an impression of a British accent.

There’s a human level where we have to be detailed and make it as human as we can make it. There are all kinds of exercises I have the actors do. I often recommend that actors do all of their dialogue in their own voice, minus the accent, just to make sure that as soon as we go and do our accent work, their performance doesn’t get eaten because it’s become a stereotype of an accent. But it’s their character and then it has this layer – the fabric of an accent – in the same way they might have a specific walk or posture for that same character.

GL: You’ve worked with a lot of the same actors on different projects. Is this common for dialect work – an actor and a coach will develop a good working relationship and the actor will request your help on whatever their next project might be?

KC: That happens very frequently. That’s a huge part of it. I have a client that I’ve done 10 films with and another that I’ve done five films with; I have a client who will never do a single audition without working with me first. Actors do a lot of heavy emotional lifting and if I’m on their team, it becomes an important creative relationship. So, very frequently, you get to the point where an actor will trust me. I know how they work, and I can just help them to get where they need to go as fast and efficiently as possible, and getting in their way as little as possible, so they can just concentrate on their artistic thing.

So, yes, there are a lot of repeat customers. That happens on the production side as well. A producer will just be like, “I like the vibe that Kohli has in the room with my actors.” Then they will hire me over and over again. Of course, I send out resumes and make phone calls and pound the pavement, but in the seven or so years I’ve been doing this for film and TV, I have been able to wait and someone will call me. Then, someone else will call me – “I heard you’re so and so’s coach and they’re my best friend and now I want to use you!”

New work can spiral out from things that way too. Sometimes it is a very personal thing, one-on-one, and an actor just wants to run their lines with me. Sometimes we spend a lot of time talking because I want them to tell me who or what this character is to them, so that I can help them build an accent around the character they’re creating. It’s not about, “Well, a standard British accent sounds like this.” It’s never that black and white. It always has to be tweaked a bit for every single actor. Every actor has their own way of doing things. It’s never about me telling them, “This is how you do it.” It’s about me saying, “What’s your process?” Then, I funnel all of my work through their process. Then it becomes easier for them to incorporate it and do their emotional work on top of that.

GL: I’ve limited the scope of your work to actors, their nationalities, their accents, and how you help them to achieve other accents. But your work involves the human voice in total, which includes all sorts of sounds beyond just regional accents. What other voice issues come up that you have to find solutions for?

KC: Before I started working in film and television, I was a theater coach. I always wanted to do film and TV, it just hadn’t happened yet; I hadn’t landed that first job. Once I got that first job, film and TV is all I do now and not as much theater. But when I was doing theater, I would do a lot of what is called vocal coaching. Theater is still in this world where it’s all about the voice of the actor.

I do a lot less of that now in film and TV, but it’s still a thing that happens, because let’s say an actor might be in touch with me because they are, not necessarily doing a different accent, but they just want to vocally realize their character and make sure it’s a different voice than their own. They want to make sure the voice represents the character. Here’s a simple way to think about it: Let’s say somebody is really uptight. The character is written and they’re just crazily uptight.

A very simple way to vocally manifest that, for some people, might be that the person talks in a short, clipped way. Or, they talk very quickly. Or, maybe they have throat tension, so it gives them a tight sound to their voice. Or, somebody’s elderly and a chain smoker. Or, the person is incredibly relaxed all the time. Or, the person has two sides to their personality that are entirely distinct. How do we show those different parts vocally? There is a whole branch of dialect work that’s also vocal and I always address that anytime I’m coaching. I also have to figure out with the actor where their voice “lives,” at what pace they’re speaking, if it’s relaxed or fast, are they monotonous, or do they have movement in their voice?

GL: When you talk about where the voice “lives,” what are you talking about exactly? I’m thinking throat, gut, stomach – is that what you mean?

KC: Yeah, kind of. Sometimes. You are right. For some actors, it can be really abstract, right? We might actually be as abstract as, like you said, the gut. We all know that your vocal chords are located in the middle of your neck, but for some people we actually talk about speaking from their heart, or the top of their head. For some actors, it’s more technical because we’re actually talking about placement and where the voice is vibrating. Are we using the forehead resonators, or the cheek resonators, the nasal resonators – where are we actually vibrating the voice in the body? Where are we placing it in the mouth? Is it in the front of the mouth, the back of the mouth, is the tongue moving a lot, do they even open their mouth when they talk? For some actors, all of this comes up, so we go in that direction with it. For some people, I’ll say, “Speak like you’re purple!” “OK, I’m purple!” [Laughs] It’s really about however they respond and whatever their vocabulary might be; that’s how it’s going to get figured out.

GL: Are you ever approached by an actor who just wants help finding their own voice, or their “acting” voice, because they’ve just started out?

KC: Absolutely. When I was teaching at NYU, I would not only do dialect classes, I would do speech classes, which is very super-specific about articulation – learning how to really articulate all of the different sounds and it’s all very muscular. Then there are vocal, or voice classes, which are very much about the sound of your voice – breathing, how to not blow out your voice, etc. Essentially, the most-distilled version of it is: What’s your actual voice versus what is your voice that has been shaped over time?

How can we strip away some of the habits and tension that you’ve developed over your life? Once we do that, all of a sudden, a person’s voice will become more open, clear, and emotionally expressive. So, that’s something that I certainly still do. But I’m also so fortunate to work with some of the absolute best actors that there are and they’ve already done all of this work I’ve described. We get to explore their character together, but I have worked with some actors who are just masters at using their voices, so we’ll talk about it to make sure everything’s working and they’re comfortable, but it’s pretty awesome when you have these people and you’re like, “How many BAFTAs can one person win in a lifetime?” And I’m like, “I definitely want to work with him!”

GL: Let’s talk about The Affair. Most people who are fans of the show probably don’t even realize the two leads are actually British. That means you’re good at your job. How did you get a couple of Brits to sound like they’re from Long Island?

KC: Ruth Wilson’s character on The Affair is from Montauk, born and raised. Dominic West’s character is originally from Pennsylvania and then he moved to New York. Ruth and Dominic are incredible actors and they’re masters of their voice. Plus, they work incredibly hard. They also have different accents in real life; they don’t have the same British accents because they’re from different places. They both have had a lot of drama training, drama school, and huge careers in England. Big careers here.

For The Affair, we were going for different things. Frequently – this is pretty common – I’ll talk to the showrunner, in this case, Sarah Treem, who is also the writer and creator on The Affair. We had an initial conversation and she told me what she wanted. I read the scripts. I talked to Showtime and they tell me what they want. Ruth and Dominic tell me what they want. And then we funnel it all through that process. And, frequently, as is the case with a lot of shows, nowadays, we don’t actually go 100 percent. For example, the Allison Bailey character isn’t 100 percent like a Montauk sound. I went to Montauk, I recorded all these people from there, I broke down the accents, but the accent was too strong for a general American audience. So, when that happens, we sort of tweak it. We take a look and say, “What are some of the little tiny things that we can add. What are some sensibilities that you have that you like from this sound or that sound?”

GL: You also coached a Brit to sound as if he’s from Yonkers for Billions.

KC: True! I coach Damian Lewis on Billions and it’s the same way with him. His character is from Yonkers, New York. So, I got some awesome recordings of these guys who are the same age as the character and they do similar stuff, they’re from a similar background as Damian’s character. I did a lot of interviews with them. Then we listened back to them with the showrunners. They were like, “These are awesome!” I was like, “I know!” [Laughs] But they were such strong accents – the heaviest.

So, we decided together, “OK. Let’s do about 5 percent of this accent.” Then, we do it and people are like, “This accent is so nuanced and detailed. What a specific regional sound!” Because going for an accent at 100 percent is sometimes fine and super fun for me as a dialect nerd. But it’s so rarely the appropriate approach, because there is so much storytelling that has to happen. You have to be careful that the dialect doesn’t somehow become the show; or become the character. That’s one way to make sure that doesn’t happen – making sure it’s nuanced, realism-based, and then it’s curated. I will literally curate the sounds that they’re going to do with the actors. We’ll build these materials, accent vocabularies – “These are the sounds that you are doing. What do you think?” Sometimes we might decide an accent is too strong even if it’s perfect and sounds like an actual person who has that accent in real life. But we might not use it for a certain character because that’s the difference between being spies and being in a story. You have to relay the message too.

GL: And if the accent overwhelms the message, or the story, you’ve not done your job correctly.

KC: Yeah, exactly. It has to all work together and be a good blend. There are so many components, right? Costume, hair, makeup, set design, art direction – it all has to work together.

GL: The way you’ve described the voice, it’s almost as if you’re looking at it as if it were a color palette. Something might need to be “blue,” but there are countless shades and versions of “blue.” When you were talking about how much “Yonkers” to use for Damian Lewis on Billions, you could have been describing a color, or how “blue” you wanted something to look. It’s like mixing colors until you have the shade you want.

KC: That’s right. And there are situations, for sure, where you’re really doing 100 percent of an accent, but so much of the time that isn’t the case. I’m dealing with the person who is the lead in the show, or the lead in the movie, and they so rarely want a full-blown mega accent. Also, America is humongous, right? There’s 330 or 350 million people here and our accents are constantly evolving. They’re so different from each other.

Let’s say I grew up in the middle of Indiana, or southern Florida, or west Texas. I’ve watched a bunch of TV, but I might not have heard some of these sounds before. Take The Wire, for example. Going back to Dominic West, although I didn’t coach him for that show, but that show was revolutionary for people like me and for dialect standards. They really used an incredibly authentic Baltimore (and surrounding area) accents. That’s a very, very strong accent and it’s not a huge population of people, so not too many people in America had ever heard that accent before. For some people, it was like, “Why does Proposition Joe say his O’s like that?” It’s because they were half coaching and half using people and actors who were really from that area. And it was amazing.

It was the fabric of the Baltimore sound. To really do it was part of why that show was so amazing. But even though it turned out awesome, that sort of thing is rare and unusual. But that’s one of the best shows ever. So, I don’t think it hurts. I think it’s great!

GL: Just listening to you answer some of these questions, it’s obvious that you are a teacher. You have been doing this for quite some time, yet you sound as excited as if you just landed your first job. You encourage my questions, you take time to explain some complicated concepts, and when I guess something right, you actually sound genuinely pleased that I’ve learned something. Is this why you teach?

KC: Oh, yes. You literally just checked every box for all the reasons why I love my job. I love helping artists. I love helping actors and storytellers get where they need to go. I always tell all of my actors, “I’m just one of the spokes on their wheel.” And I love that. I love being a part of these wonderful, incredible artists, being one of the members of their team that just helps them get to this artistic place. I find it really rewarding on a personal level. Just getting to know my clients too, like, “Here we are Skyping again and it’s three in the morning, ’cause you’re in Eastern Europe and I’m in my pajama pants in New York just doing our thing!” [Laughs]

And the amount of times where I’ve been, like, you name it, in some city, I’m bleary-eyed, or if it’s freezing outside and I’m in a trailer, or it’s raining. Still, I’m like, “I really believe in this story. I believe in you as an artist and an actor. I’m just here to support you.” It’s a very personal process. It doesn’t work if they don’t trust me. But, yes, to answer your question, I am definitely patient at my job. At some point, I managed to become incredibly efficient without being bossy. I just love the camaraderie of it. I love to be a part of the storytelling. I love being a part of these incredible performances.

GL: You come from a theater background, how much do you enjoy being on the set of a motion picture?

KC: The amazing part of being on a film set is that I’m 30-feet away from you and you’re doing 10 takes of a scene and I’m sitting here watching this live, theatrical moment that no one at home is ever going to see, but I get to be part of that. I love it. I’m very fortunate. I’ve had such wonderful humans and artists that I’ve been able to work with. Also, they know it’s them up there. They know it’s not me. Half the time, on set, most people don’t even know that I exist or coach. I always tell my clients that I am there to serve them. Any actor I work with, I always say, “My job is to help you. I work on this production and they are paying me, but my job here is to help you in whatever capacity that’s going to help you ace this part of this job. You don’t have to worry about anything. You just have to go up there and kick booty.” [Laughs]

GL: It seems you have a lot of repeat clients: Even Hewson (The Knick) and Bella Heathcote (The Neon Demon). Is it common for dialect coaches to strike up lifelong working relationships with a handful of clients?

KC: Bella and I have been working together for about six or seven years. One of her first big American films was a job that we did in New York. We just hit it off crazily, so she always asks to work with me. Basically, every job she does, I’m on it too.

I’ve been coaching Eve since before she was booking roles. I worked with her when she was just auditioning. When she started booking, she was like, “I’m calling you back!” So, I coach her on just about every job she does. Sometimes it’s an agent that will call me. They’ll go, “Oh, you’re my other client’s coach. Will you try working with this person?”

The acting community is actually incredibly small, especially when you’re talking about foreign actors. Sometimes the situation is like: This Australian actor is friends with this other Australian actor and then they hit me up with an Irish actor they both know and then he knows more Irish actors and so on [laughs]. It becomes very personal.

I’m not interested in drama or stress. It’s a very stressful environment with long hours, it’s high stakes, people are giving a lot of their time, they’re away from their families, lots of money is riding on it. I try to be really Zen and make sure I’m empowering the artists and the team that I’m a part of, because, let’s be honest, this is not rocket science. It is not brain surgery. It is literally: We can take the time, we can figure out these sounds, and then the actor can go up there and do an incredible performance.

GL: This happens to me when I’m watching a film and someone is doing an accent, so I can only imagine that with your ear…

KC: I already know what you’re going to say! It does. It happens all the time! [Laughs]

GL: Well, for you, is it like an opera singer hearing someone else hit a wrong note? I can imagine you in a movie theater, “Ouch, some British leaked out there. And this guy is supposed to be from Ohio? Hacks!”

KC: It’s true. I always notice, but here’s the thing that I think makes me well-suited for my job. I love the voice so much. I love accents, so even if I’m watching something and even if the accents are not that good or, “Uh oh, you can tell that didn’t work out as well as everyone probably hoped it would!” [Laughs] I still think to myself, “This is great. Everybody here is trying.”

I may or may not know the coach that was there, or the actors, or the situation – but people are trying. They’re getting out there, they’re being creative, they’re bringing art into the world. Hey man, that’s awesome. It’s true that nothing slips by my ears, but I’m never offended.

GL: You’re also a musician. How does that fit into all of this? That’s another artistic pursuit that relies quite a bit on one’s ears.

KC: Well, you know how it is. My dialect coaching is very behind-the-scenes and I really like it that way. I will hide. I’m in the back. I’m one of the last credits ever in the scroll, you know? [Laughs] But, I also sing. So, I also use my voice and my ears for my more upfront creative outlet, which is music. They definitely help each other because it helps my ears and my voice stay strong. I treat them both really well. It’s fun to have that separate thing, because I so desperately love to be part of a creative community. So, there’s the version where I get to be the person who supports another person. Then, there’s the other side of it where I get some people to support me and I can do my thing that’s a little bit more upfront.

GL: Is it safe to assume that you think being creative is a real job?

KC: It is definitely a real job. It only happens because of hard work and discipline. I have a very strong work ethic. I don’t take failure as an option, or setbacks. If something sets me back, I course-correct. I’m going to keep doing this, because this is how I like to live my life. I like to be a dialect coach, I like to be a musician, I’ve got a family – those are the things that I do and I like it that way. Sometimes there are droughts – I don’t coach as much, or I don’t have time to sing. But I just keep swimming!

All photos of The Affair and Billions courtesy of Showtime.