Published Date: 06-03-20

By Justin Sanders

[All photos courtesy of Julian Fort]

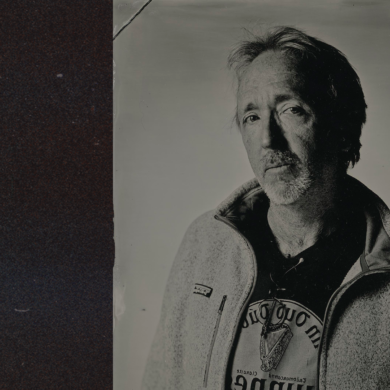

When we last spoke with Julian Fort, in September of 2018, he had recently completed his first feature film, The Midnighters. With a powerful lead performance from Leon Russom (The Big Lebowski), the indie thriller made the most of its shoestring budget and has proved to have some staying power.

More than a year and a half later, it’s still “picking up a little bit of steam,” Fort says, catching up with CreativeFuture from his home in Los Angeles. Alongside Russom, the film also features recognizable talent such as the late actor, John Wesley, and Costa Ronin, whose star is on the rise thanks to recent turns in shows such as The Americans and Homeland. The cast, along with Fort’s sharp writing and direction, has kept The Midnighters “ticking up on the streaming networks,” he says, “which is really a good sign.”

Julian Fort and Costa Ronin

With momentum on his side, Fort had even procured some seed money from an investor to make his next film, and had begun writing the new script, about “the bonds of trust and how far they go, all set against a pulpy modern crime world.”

Then pandemic struck, and Fort’s aspirations, like those of most creative people, were set adrift. A longtime security guard for Paramount, he is now, with the studios closed, at home. Though he has plenty of time to write, “it’s been really hard,” he says. “I’m definitely not an at-home writer and so I haven’t been writing that much, even during the crisis.”

A creature of habit, Fort has always found his muse by changing his location, often working in coffee shops and drawing inspiration from the many other creatives who flock to them. Starbucks was even where he met Leon Russom, striking up the friendship that led to them working together.

“Not having that is really a drag,” Fort says. “I feel homeless in the writing sense of the word.”

Desperate to shake things up, Fort has found himself driving to scenic viewpoints along Mulholland Drive and scribbling a few pages in his car. “It feels really weird,” he says, laughing, “like I’m that guy who’s living out of his car now. But there is something about getting somewhere where there’s a vista to look out over. The change of scenery allows me to stay sane.”

To that end, Fort has also been doing a lot of hiking in recent weeks. It’s calming and helps take his mind off the stress of, well, everything. Up on the trail, the breeze against his face, it’s possible sometimes to feel less frustrated and scared, and more grateful and optimistic.

“Now that I’m further out from The Midnighters, I’m able to be prouder of the picture,” Fort says. “I saw its imperfections and flaws in such stark contrast when it was fresh, but now I’m able to be proud of what it is, and what it means to people. I’ve gotten a lot of nice messages and reviews from people who get the film.

“That’s a great feeling,” he continues, “and I’m happy to allow positivity to sweep me away right now.”

We salute Julian Fort and all creatives in our community as we navigate these uncharted waters. Read our original interview with him below – and, as always, #StandCreative.

From September 26, 2018

For filmmaker Julian Fort, cinema wasn’t so much an interest growing up as it was a part of his DNA. Raised in Los Angeles, he is the son of Marty Fort, who co-founded L.A.’s beloved bastion for indie film, the New Beverly Cinema.

“I was six years old and my dad had his own 45-foot movie screen,” he told CreativeFuture. “I’m sure that’s why I’m a filmmaker today.”

And yet, despite filmmaking being the most natural career extension of his upbringing, Fort took a long and winding path to arrive at it. Eschewing film school, he elected to strike out on his own, writing script after script in between shifts as a security guard on the Paramount studio lot. It was a seemingly “endless road of coming up with the right script and raising the right amount of money to make it,” he said.

The right script was inspired by a chance encounter with the great character actor Leon Russom, whom Fort befriended at the Starbucks they both frequent. Russom – a fixture of multiple Coen Brothers films among more than 100 other credits – took a liking to Fort’s writing, so Fort wrote a screenplay for him and his debut feature, The Midnighters, was born. A slow-burning bank heist about an aging safe-cracker who uses his old skills to save his son’s life, the completed film has received rave reviews and is now available on every major streaming outlet.

Made for just $80,000, The Midnighters looks like it was made for a million, but as polished as the final product is, the journey to it was rife with struggle, and even disaster. Two-thousand-pound props fell off trucks, locations fell through, and a crewmember was almost crushed by a lighting rack. Fort endured, finishing the film, but continued to face hurdles when pirated versions of The Midnighters popped up on YouTube – before the movie had even been released for public consumption.

Fort went through the process of sending a takedown notice to YouTube, which involved enduring four different screens of questions before arriving at a disclaimer page “where I had to acknowledge that if I was lying about owning my film, I could be held criminally responsible,” he said. “I actually felt like I was doing something wrong by removing my film!”

“It’s terrible the way they put it all on the filmmaker to fight this stuff. It comes down to this: if Google can write an algorithm that can tell me what I want to search for before I even know that I want to search for it, then they can damn well write an algorithm that says, ‘This is highly likely a pirated piece of IP,’ and then they can put in checks and balances to remedy the situation!”

An engaging and articulate voice for independent filmmaking, Fort was kind enough to sit down with CreativeFuture and talk process, platform accountability, and how he took the road less taken to achieve his dream.

Julian Fort (left) and Leon Russom

Justin Sanders: We have to start with The Midnighters and its star Leon Russom, who Coen Brothers buffs will immediately recognize from his iconic scene as the Malibu Police Chief in The Big Lebowski (“Stay out of Malibu, Lebowski!”) How did you end up getting an actor of Russom’s caliber for your first-ever feature?

Julian Fort: I met Leon at a coffee shop and had the fortune of becoming friends with him before I even thought that there was the possibility of us working together.

Truthfully, I was star-struck by him. His scene in The Big Lebowski is one of my favorite scenes in movies. To me, he was like Brad Pitt and just the idea that I could ask this guy to check out a script that I wrote was mind-bending.

But one day, he asked me what I was working on at the coffee shop. At the time, I was actually writing a different movie, which I’m trying to get made right now – it’s a psychological thriller about a serial killer and there is some really dark, scary stuff in it.

So, I gave that to Leon, [laughs] and then I didn’t see him for like a month. He usually came by the shop every night and I was sure that he had read the script and was afraid of me now, thinking, “What demented mind came up with this scary s**t? I’m going to a different Starbucks.”

But then one day, I hear this knocking on the coffee shop window next to where I’m working. I look up and it’s Leon. He loved the script. He said, “There’s nothing for me to play in here, but it was really great.”

I was looking to write something new anyway, so I started thinking that if Leon likes my writing, maybe I could write something specifically for him.

So, I asked him. I said, “What kind of story would you be excited about acting in?”

He said, without even thinking about it, “I would like to play a parent whose kid is in some kind of trouble.”

[Laughs] I was like, “Okay… can I set it in the crime genre?” And he was like, “Sure!”

Is crime the genre you prefer to write in?

I’m kind of all over the place, but Leon’s face is so noir. It’s a beautiful mug, perfect for a crime story. So, with that wonderful face and the little thematic nugget he had given me about fathers and sons, I structured this heist story that eventually became The Midnighters.

So, you write the script and you have a name actor on board. How do you then go out and get money to make the film?

Friends and family. I didn’t have any promise of money at all, but I felt confident that an ask to certain people in my life would be realistically entertained. I figured I could get between 50 and 80 thousand – and I was right.

Once you had the money lined up, when were you able to start shooting?

It took forever, because the script was ambitious for the money that I had. I wish I was a genius and could write a movie about two guys in a room and it would be compelling and artistically satisfying, [laughs] but I’m stupid and I wrote a bank heist.

I had the money raised for over a year. Let me tell you, it makes you start to really question yourself when you have the hardest thing to get – the budget – and you still can’t get the movie off the ground.

But if you had the money lined up, why did it take so long to start filming?

It took forever to find people who would play ball with us in terms of our locations. Everyone knows what a location is worth in Los Angeles and they want that rate.

For instance, I needed a seedy motel for one scene, and I went to this place that was literally collapsing. I had done a photo shoot there about six years before and paid $300 to use one room for the day. This time around, I would have a crew with me, so I thought, why not offer the owner a thousand?

So, I did, and she said, “Uh-uh. NCIS: Los Angeles gave me $4,500.”

[Laughs] I was like, “I’m not NCIS, lady,” but she wouldn’t budge.

It’s too bad that they couldn’t differentiate between a larger production and a low-budget indie, considering most films that get made are small indie projects like yours.

A friend of mine shot a horror film in Pittsburgh and locations were literally paying him to shoot there. The restaurant that served as one of their key locations was so excited to have a movie being shot there that they offered up the property at no charge and then sweetened the deal by keeping the kitchen staff on after hours so they could feed the cast and crew for free.

In L.A., it’s an entirely different story. Every property owner has heard the stories about big-budget productions, that just have to have a particular location. In L.A., no one knows who you’re affiliated with, but everyone potentially has a large budget. $4,500 would have been a very substantial chunk of our budget, and yet we had to fight this expectation for every single one of our locations.

Were you nervous leading up to your first day of shooting?

I wasn’t nervous – I was terrified. Before The Midnighters, I had never even directed dialogue before. The learning curve was vertical. It was a greased pole.

The terror really began in preproduction, when I found out that with microbudget features, you spend about 30% of your budget before you even start shooting. You start signing away to vendors and buying permits and all that stuff. There were times when I wanted to pull the plug and re-strategize, and when I couldn’t do that anymore and I realized that I had to ride this lit fuse all the way to the end, it got scary and it stayed that way.

Now, if someone had told me that I was supposed to feel terror and that it was all going to fall apart at times, it wouldn’t have been like a bucket of ice water hitting me in the face every day.

How did it fall apart at times?

We had an 18-day shooting schedule. First of all, movies should never be made in 18 days – and then we lost three of those days during production, so it was really 15 days.

We didn’t have a bank vault when we started shooting, because the bank no longer existed that I was going to shoot in. And it’s, you know, a bank heist film, so that was a problem. We had to build that, and we didn’t have the money for it and we just got lucky – we ended up stumbling across the bank door prop from Ocean’s 11 at a scenery warehouse and they rented it to us for a steal.

But, they didn’t tell us that we had to load the prop off the truck ourselves, and that the thing weighed like 2,000 pounds. Ten people couldn’t lift this thing. It got to the set and we had to go down for the day while we hired a union forklift driver to come and load it off.

Then on day three, our key grip almost got crushed by a lighting rack. It fell off the grip truck on to him. He tried to stop it from falling and it got him just enough to break two ribs.

The next day was the day of the Boston Marathon bombing and our cinematographer’s son had been at the finish line. So, we had to go to work not knowing if his son was okay (Ed: he was okay).

Every day, it was something that seemed like it was jeopardizing our ability to finish the movie. It was crazy all the way down the line. Always in freefall.

People not in the industry don’t understand how truly dangerous a film set can be. It’s amazing you prevailed through all that.

I knew just enough to pull it off but not enough to stop me from committing to the project. I would never make this movie knowing what I know now for the money that I had. But hindsight is 20/20.

Plus, as much bad luck as I had during production, I got unbelievable deals in post-production from my editor, and from the companies that did our sound and color. They pretty much donated at least $100,000 in post-production costs on the film. That’s why the movie ultimately works I think, because if you don’t get those finishing touches right you get something that feels very unpolished.

Switching gears here – your father, Marty Fort, co-founded the New Beverly Cinema in the late ‘70s, which has been a destination for independent film in Los Angeles ever since. What was it like growing up with a movie theater as the family business?

I mean, I was six years old and my dad had his own 45-foot movie screen. I probably saw a lot of films that I shouldn’t have at that age, but the love that my father – along with his business partner and best friend Sherman Torgan – had for cinema was indelible. I’m sure that’s why I’m a filmmaker today.

Filmmaker Quentin Tarantino took over the New Beverly in 2014. Did you or your family have any contact with him during the transition?

No, we were no longer involved with the theater by then.

However, funny story: I was in Burbank recently, meeting my girlfriend, and we’re walking and talking, and she suddenly pulls me back because there’s this muscle car coming down an alley that stops right in front of us.

It’s Quentin, driving the yellow Mustang that he got when he made Death Proof. I went up to the car and knocked on the window.

I could see he was not into me approaching him, but he rolled the window down and I said, “Hey, Quentin, I just want to tell you – before the light changes and you drive off – that my dad opened up the New Beverly with Sherman Torgan in 1978, and I want to thank you for what you did, because it’s so important to so many people.”

I could see all the tension melting away from his face, and he goes, “Thanks, man!”

Then the light changed and he took off.

[Laughs] Only in Los Angeles! So, you could watch movies on a big screen whenever you wanted as a kid. When did you start actually making them yourself?

I was making videos and Super 8 films as a teenager, but not as many as I would have liked to. When I was 19, I made some artsy-fartsy black and white shorts, but honestly, just trying to figure out how to get into the film industry took the biggest chunk of my energy and time.

Did you ever consider going to school for filmmaking?

Early on, I started writing a short film that was to be my sample for an application to the American Film Institute (AFI) – but it quickly evolved into what felt like a great idea for a feature.

So, I said, “Screw film school. I’ll just make a feature on my own.”

That became this endless road of coming up with the right script and raising the right amount of money to make it.

How did you support yourself while you were trying to get a film off the ground?

A friend of mine was at Paramount at the time and 9/11 had just happened. He said they needed security and I thought, “Well, I want to make movies. It couldn’t be the worst job in the world.” It paid really well and it got me on the Paramount lot with 5,000 Paramount employees I could network with.

I imagine working security at a bustling studio lot was very inspirational for an aspiring filmmaker.

Absolutely, especially during the first 10 years I was there. I’ve dialed it back in recent years to work on filmmaking, but early on, the lot felt like when you watch an old movie about the wide-eyed kid who goes into a Hollywood studio, and there’s a guy in an astronaut costume walking around next to an elephant, who is being led down the street by a marching band. That kind of magic was there.

What was the trajectory of your filmmaking career during those 10 years?

Slow. By my third script, I had actually gotten a production team on board to make the film, but we were always about six months to a year behind the curve.

I would have a distributor saying, “If you get me this actor, we’ll give you the money” – well, we were no one and we had no agents and no managers, so it would take us a long time to get to the actor. Then we would get to the actor. We would get a letter of intent and we would go back to the distributor – but then they would say, “Well, we just bought three movies with that actor, so now you need to also get this actor and this actor.”

I wasted a lot of time that way. But in hindsight it’s fine, because I didn’t know what I was doing and I still needed to learn. And, I became a much better writer through that process.

Seeing as you didn’t have any representation or cred within the industry, how were you getting name actors attached to projects during that time?

Sometimes, what you don’t know gives you the freedom to do things that you wouldn’t do if you did know.

The Screen Actors Guild (SAG) at the time had an open-door policy. You could call SAG, tell them the actors you were interested in for your project, and then they would give you the agent’s phone number for each actor. My producing partner at the time would call those agents, and he was really good at getting the scripts read and getting the actors to sign letters of intent.

I wish I could do that now.

Why can’t you?

Now, the independent film industry has sadly become the market industry of the ’90s, in the sense that instead of getting a million bucks with more under-the-radar actors like James Russo and Matthew Modine attached, you have to go out and get Brad Pitt – and even that will only get you maybe a couple million bucks.

I’m struggling with how to even get to talent of that caliber because I’m not represented right now.

You made The Midnighters, a respected feature with somewhat known actors – shouldn’t that be enough to garner an agent?

Probably, but at this point, I think I probably have a better shot at leveraging the contacts I’ve made and continuing to make my own stuff. The days of some agent taking you under their wing and going, “Kid, you got moxie. Come with me, I’m going to develop you,” are gone.

Is that because there is so much content in the world, they don’t want to invest in an unproven talent?

I made a movie for $80,000 that looks like it was made for a million, and I only did that because of technology. But the tradeoff is that the gates opened up and now anyone with an iPhone and Final Cut Pro can make something that passes for a movie.

So, you have this enormous ocean of media and you have a dwindling audience because there is just too much to watch. Then on top of that, you have a younger generation that’s coming up who thinks that everything should be free and instantaneous, so you’re vying for a much smaller portion of the audience who is willing to pay. Then that revenue can be fractured even further by piracy – so, yeah, of course agents aren’t going to risk representing someone who isn’t already bankable.

Have you experienced piracy with The Midnighters?

I was on YouTube about six or seven months before The Midnighters was officially released, and there were already several links for the film that all led to pirate sites. I had been expecting that to happen once the film was released, but I hadn’t expected it to happen before it was released – all we had done with the movie, to that point, was put out screeners and featured it at some festivals.

So, I went through the process online of having YouTube take down the links to the film. I had to go through four different screens of questions before I got to a legal affidavit – a whole disclaimer where I had to acknowledge that if I was lying about owning my film, I could be held criminally responsible.

I was like, “Wow. This is insane.” I actually felt like I was doing something wrong by removing my film!

It’s terrible the way they put it all on the filmmaker to fight this stuff. It comes down to this: if Google can write an algorithm that can tell me what I want to search for before I even know that I want to search for it, then they can damn well write an algorithm that says, “This is highly likely a pirated piece of IP,” and then they can put in checks and balances to remedy the situation!

While we’re on the topic of scary technological disruption, I often worry that our attention spans are becoming so fractured, future generations won’t even care about cinema.

Movies are among the most expensive artifacts that humans create and we line up to see them, so there’s something going on there that we desperately need, and yet the experience of seeing a movie in a theater is sort of being taken apart because the world is evolving.

What’s at stake is deeply ingrained into our collective psyche. The communal act of sitting down together and watching a story and embodying that story and learning from it is something we’ve had since the beginning of time. We perceive the world through story and myth and drama. It’s hardwired into our actual neurochemistry. It’s absolutely essential and it’s under assault, which is baffling, infuriating, and tragic.

These are scary times for filmmakers and film-lovers, but it seems like you’re not giving up any time soon.

Not at all! With The Midnighters, we were so limited in our resources that I had to put in every usable frame of footage – and we probably only had 30% usable footage from the complexity of shooting a movie with no money.

I can’t even imagine what I could do if I had even 50 or 60 percent usable footage. I just want to be turned loose at this point.

Turn me loose!

What advice would you have for readers who hope to be “turned loose” themselves – who dream of making an indie feature with no studio backing, as you have?

The one thing I wish I knew before I started the whole process is this: It almost always feels like it’s falling apart in one way or another.

And that’s okay. You can’t escape it. Every person, every location, and every situation bring an almost infinite complexity to the shoot day that expands in ways you never could have imagined. You have to adapt in real time to the changes that are flying at you and, at first, that can feel like your production is collapsing in front of your face.

But actually, this sense of collapsing can bring about innovation that you would never have been able to come up with had you not been faced with the daily onslaught of seemingly impossible hurdles that you have to conquer if the film is to keep going.

So just remember, if you ever get that sinking feeling that your plan is falling apart on you – it’s most likely not. It’s just a feeling, and perhaps the universe is providing you with an opportunity to generate an even better plan on the fly.

All videos and images courtesy of Julian Fort