Published Date: 08-28-19

By Justin Sanders

Puberty is not for the faint of heart. We know this. We remember the hormones and the emotions, and the changes in our bodies that sometimes made us feel like strangers to ourselves. It’s a challenging, discomforting rite of passage that we all go through – and yet rarely does puberty get its proper due in the cinematic arts.

That’s why Dutch filmmaker Nienke Deutz’ animated short film, “Bloeistraat 11,” is such a revelation. Telling a wordless tale of two young female friends on the brink of adolescence, Deutz renders her girl characters with a shimmering stop-motion translucence that quite literally exposes their fraught vulnerability. It’s a deceptively languid, sneakily heart-wrenching series of vignettes set in a single location, and packing more emotion, history, and character development into 10 minutes than many feature films do in 90.

Deutz’ potent combination of nuanced storytelling and artful craft was more than enough to earn “Bloeistraat 11” the CreativeFuture Innovation Award at this year’s Slamdance Film Festival. It was one of many honors the film has picked up on the festival circuit, including a coveted Cristal for best short film at France’s renowned Annecy animation fest. This fall, it will screen in select theaters across the U.S. as part of the GLAS Animation Festival’s ANIMATION NEXT compilation.

“Making this film very physical was a way to explore how we can empathize with animated characters,” Deutz told CreativeFuture from her apartment in Rotterdam. It was but one nugget of many in a lengthy interview about how she developed and funded the fascinating, beautiful technique that helps make “Bloeistraat 11” feel like “the epitome of what you can do as a child when you’re crafting.”

JUSTIN SANDERS: First of all, I must ask, how on earth do you pronounce “Bloeistraat 11”?

NIENKE DEUTZ: [Laughs] It’s “blow-ee strawt” and then “eleven” in Dutch is “elf.” I like diversity of languages so I thought, let’s go for a Dutch name that nobody can pronounce.

JS: And what does it mean?

NK: The full English translation is simply, “Bloom Street 11.” It’s the made-up address of the house where the film takes place. I liked it because there is a very obscure Dutch dialect in which “Bloei” also means “to bleed.” And blood, as you know, features in the film at key junctures.

JS: Yes, the characters in “Bloeistraat 11” are rendered as transparent figures, and we sometimes see emotional beats manifest as literal flesh and blood. You have another, much older short on your Vimeo page that is also called, perhaps not coincidentally, “Bloom,” and that also revolves around a similar anatomical motif. Where do you think this interest in visually “opening up” the inner workings of the human body comes from?

NK: Good question. I guess I am very much fascinated by our relation towards our bodies – that we are not really connected to them even though we would like to think we are. Even the most body-conscious people can grow sick without noticing. I can connect to my skin and my outside, but how often do I actually think about my liver or any other organ? I find this very fascinating.

In the case of “Bloeistraat 11,” I had an extra reason to use the body so explicitly: I think that it can sometimes be a bit hard to feel empathy for an animated character. We do not easily see the animated character as a representation of a human, so things can feel a bit far off.

I wanted to see if there are ways to feel more engaged with an animated figure. I had this idea that by showing the physicality of a character very explicitly and even making them go through unpleasant stuff, you can create a way to connect more easily with them. The unpleasantness can almost cause a mirroring reaction in our own body, which makes us understand that what we see on screen is not just lines or a puppet, but the representation of a human body.

Making this film very physical was a way to explore how we can emphasize with animated characters.

JS: And that physicality takes on an extra layer of vulnerability because you are presenting two women on the brink of adolescence.

NK: For me, the friendship between two girls at the onset of puberty is like a symbol for a relationship between two people and how we are very unable to communicate sometimes. There is an under-the-skin feeling that you have sometimes when you are very close to someone at that stage of life. It is kind of the first moment when you make a relationship with another human being entirely on your own. Before that, relationships are not something you actively choose. And these first friendships that you make in puberty are kind of like the tryout for other relationships that you have later in life.

One of the main reasons why I chose this specific time period was because I knew from the beginning that I wanted to work with crafting materials in the animation. I think the aesthetics of very simple crafting materials fits very well with the beginning of puberty – with these moments at the end of childhood. I realized that this film should almost symbolize the epitome of what a child might be able to achieve when crafting.

JS: You bring those “crafty” materials to life in a very unusual way in “Bloeistraat 11.” How did you develop the animation technique utilized here?

ND: What I really love to do is build sets, and models. It was very important for me to make the space of the house where this friendship would take place feel very present – for the viewer to understand the physical space of the house.

So, I was designing this set, building it from cardboard, and at the same time, I was drawing, making puppets, trying to figure out the look and feel of the characters. I started doing some very simple black line drawings on a piece of plastic, in pencil, and put them inside one of the sets. I animated the figures on just a two-second loop and noticed that light would flicker behind the clear plastic. It was beautiful, but very inconsistent. The body during puberty is different almost every day. You develop breasts, hair grows in strange places. Your body doesn’t have a fixed form, and this animated plastic, with the light behind it, didn’t have a fixed form either. That’s when I thought, “This is great. I can work with this.”

JS: When you say “animated the figures,” what do you mean in technical terms? Is it stop-motion? 3D animation? A combination?

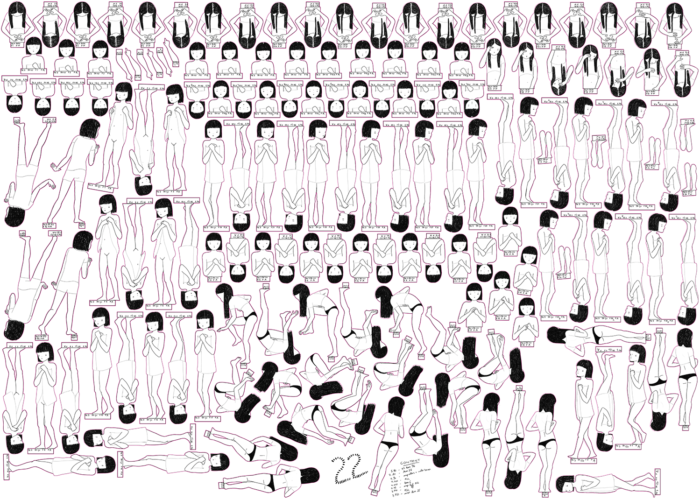

ND: Everything you see in the final version is done in camera – there is no 3D used. A common way to work in stop-motion is by using puppets. You change their position every frame and, when played at speed, this forms the illusion of movement. But another way of working in stop-motion is by using “replacement.” This means you have, depending on the frame rate of your animation, 12 or 24 “versions” of a physical character or object where each version differs slightly from the previous one.

I used the replacement technique, which meant that, at 12 frames per second, we had around 6500 cut-out plastic frames representing the characters across all 10 minutes of the film. These frames were first drawn in an animation program called TVPaint, and as a reference for the sets, I used simple models made in a 3D program called Blender. But this was just to get an idea of how the characters related to the space.

When it was time to do the in-camera 2D animation, all of the 6500 separate TVPaint drawings were exported and placed on a big image file to print onto 100x140cm plastic sheets.

Once printed out, these images were then cut out from the plastic, painted, and sometimes even outfitted with another object or piece of fabric. Then they were placed in the set and filmed, one by one, frame by frame.

JS: Here is where my mind goes when you describe such a fascinating process: How the heck did you print and cut out 6500 plastic figures?

ND: They were cut out by a machine. At I first I was very purist about it: “Everything has to be done by hand.” But the very first test that I cut by hand was insanely difficult, so then I thought, “Actually, I don’t want to kill myself. What can we do with automation?”

I found a place in this tiny Belgian village, a company that just does cutting and printing with plastic. I had to search for it for a long time!

JS: Speaking of time, how long did it take you to make this film overall?

ND: From the start, it took me three years. One year of development in between doing other stuff to make money, and then one year waiting to get all the funding ready. And then the last year was a full year of production.

It’s crazy right? This is how animation works. If someone would have said to me beforehand, “Hey, you’re going to spend three years of your life making a 10-minute short about two girls in the beginning of puberty,” I would have laughed and said, “Never!”

JS: How did you get the funding to sustain such a long production window – and for an experimental animation short, no less?

ND: I was actually really lucky. When I finished my master’s degree in animation, I sent my thesis film to a festival where it was automatically placed into what’s known as the “Wild Card” competition, which includes entries from all the Flemish film schools, in categories such as live-action, documentary, and of course, animation. The winner in each category wins a subsidy package for a future project.

My film, which was about kids playing a Belgian game similar to “Red Light Green Light” in America, was very experimental. But I was lucky to have a jury that was interested in something a little different – and I won!

Then of course I thought, “Oh, this is so much money,” but when I went to a producer about a year later, they said, [laughs] “This is not nearly enough money.”

So, we then successfully applied for subsidies from the Netherlands Film Fund and the Wallonia-Brussels Federation’s cinema and audiovisual center. It took a while for the money to come in, but still, I feel very lucky to live and work in countries that support filmmakers in this way!

JS: How did you go about finding a producer for the project?

ND: I just thought about which people I would like to work with, and there was a company called Lunanime that I thought would be a nice fit. Their main producer, Annemie Degryse, had been on the Wild Card jury, so they were aware of my work, and I just wrote them an email.

I had never worked with a production company before so I did not know what to expect. But Lunanime, and Annemie, gave me a lot of trust. She let me do what I wanted to do even though it was not the most efficient or easy or safe way to go.

JS: What is in it for Lunanime to partner with you on a project like this? Obviously, it’s an interesting project with a cool artist like yourself, but creative satisfaction aside, how can they justify devoting time and financial resources to an experimental short?

ND: This is a good question because for sure there is very little financial benefit in it for them. It can give them some good exposure at festivals if the film does well, but mostly, short films are a way to give new filmmakers the time and experience to develop. I think some countries in Europe still believe in nurturing this kind of non-commercial filmmaking. A lot of bigger production studios also do smaller, more experimental stuff on the side. And who knows? Maybe in the future the up-and-coming directors they partner with will develop a bigger project with them, like a series or feature film.

JS: For a feature film backed by a studio or production company, there is generally a release date they are trying to finish in time for. But how does it work for an experimental short? Did Lunanime give you a hard deadline for the completed film?

ND: The only deadline I had was that we had booked studio time to do the stop-motion part, but it took a lot more time than we had anticipated. Another production was coming in and we were going to have to leave, so I had to work long days to finish in time. We managed in the end, but it was very stressful. Also, I was just so tired, working around the clock, and it’s hard to be creative in that state.

JS: Were you working a day job to boot?

ND: No! I was able to do this full time. Very nice! Even though I was dying from exhaustion every day, I felt very privileged.

JS: How about now that you have completed the film? Do you get to work on your next one full time?

ND: I will once we get our funding and start production. But making short films is not really going to make you a living, so that’s why in between productions I also work as a freelance animator, director and teacher of animated film.

JS: Where are you from originally?

ND: I’m from a small city in the middle of Holland called ‘s-Hertogenbosch. It’s a funny name, even in Dutch!

JS: Did you always want to be a filmmaker growing up?

ND: I wanted to be either an inventor or a writer, so I’m kind of close now!

But actually, I was never someone who really had a specific aim of what I wanted to be. After high school, I did a one-year theater study where I took classes in everything from set design to costume making, to acting and singing. I loved all of it – except the acting and singing – but mostly I loved coming up with stories and thinking of how to execute them using sets and costumes.

JS: Did you think you would have a career in theater?

ND: Yes, I wanted to go to theater school to become a director. But I had to do entrance auditions and was extremely nervous for the acting bit, and I did not get in. I was devastated actually. But then I got accepted to art school and decided to try that. When I learned that there was a video department at my school, things fell more into place. I really feel, working as an animated film director, that I am precisely where I want to be and doing what I really love.

JS: How so?

ND: With animation, you get to think on a completely different time scale. The outcome of “Bloeistraat 11” is just one 10-minute film, but for me it felt almost like I did six different projects, each one requiring a different set of skills. I researched a lot, and then there’s the writing, the storyboarding, the directing, the working with other people. There are always more layers than I am expecting in animation, from painting a lot of frames to the narrative content. It is never boring, and it’s very nice to pursue each different layer at a slow pace.

I worked for a newspaper last summer, making animated gifs and other content for their website – and the pace is so fast. It was interesting to do but I really craved the luxury of being able to work slower and really dissect something completely. Sometimes I will see how much content other creatives generate, and I feel like [laughs], “cool, I’m doing this 10-minute film that will be done in three years.” But that’s what animation is. You make 12 or 24 frames a second, and it’s all super fascinating and a very big challenge. And I really love doing it.

JS: What advice would you have for other aspiring filmmakers who are thinking about testing the animation waters?

Do it! Experiment! Try different stuff and find your own voice. For inspiration, look around you, talk to people, watch movies, go to museums and read books, look at the world and not just at other animated films. Stay close to yourself and what brought you your initial enthusiasm. Animation can have a long learning curve because of its slow pace, so have patience. Also surround yourself every once in a while with people who share your interest, and geek out together!