Published Date: 03-29-17

By: Gregg LaGambina

Sixth in the series.

When you sit down in her office and speak with Lulu Zezza about her job as a physical production executive, stories about accounting – budgets and overages and balance sheets – are to be expected. But, then, quite unexpectedly, she will tell you about the hurricanes and the helicopters, the rescue missions, and her trips to the very bottom of the world (Tierra del Fuego, to be exact) in a desperate search for snow to finish filming The Revenant. As an aside, she will also mention that making The Revenant took five years.

As she tells her tales of moviemaking, Zezza keeps a calm demeanor, one she has likely refined over the years to address emergencies and unexpected crises with a clear, problem-solving mind. It is this quality that has propelled her career, earning her the trust of studios to help shepherd projects such as Birdman and Cure for Wellness through to completion – on budget and on time. She is also a champion of strong copyright protections and a board member of the Content Delivery Security Association, always seeking new ways to protect the work of artists from digital theft.

CreativeFuture recently visited with Zezza to talk about why she abandoned her aspirations to become an actress, enrolled in New York University instead, took her father’s advice to learn business alongside film production, and how an afternoon of photocopying set her entire career in motion.

Gregg LaGambina: What is a physical production executive?

Lulu Zezza: A physical production executive is a position at almost every studio. Usually, there are several of us, depending on the size of the studio. We’re responsible for the mechanical making of the film. That’s everything from budgeting to planning. We answer “How are we going to make this film?” – and that includes, where, what format, how long it should take, the type of crew that we need. And then, once we’ve engaged people like the line producer and the production team, we’re there as sort of an overseer, as a sounding board for ideas, as an advisor, and to make sure that the production is staying on track and producing the movie that we intended to make, ideally for the cost that we intended to spend on it.

Lulu Zezza: A physical production executive is a position at almost every studio. Usually, there are several of us, depending on the size of the studio. We’re responsible for the mechanical making of the film. That’s everything from budgeting to planning. We answer “How are we going to make this film?” – and that includes, where, what format, how long it should take, the type of crew that we need. And then, once we’ve engaged people like the line producer and the production team, we’re there as sort of an overseer, as a sounding board for ideas, as an advisor, and to make sure that the production is staying on track and producing the movie that we intended to make, ideally for the cost that we intended to spend on it.

GL: You say, “ideally.” What happens if you don’t meet that ideal and overspend?

LZ: Sometimes we do discover that what we thought it would cost to make the film was not enough to make the movie that we want. That’s what we call an “approved overage.” We are saying, “You know what? We do want more, so we’re going to spend more.”

GL: You are responsible for making the decision whether or not the extra expense is worth it?

LZ: Yes, because there are times when an overage is asked for because things aren’t being managed well. That’s not an approved overage and our job is – as much as possible – to prevent that from happening.

GL: How does someone become a physical production executive – a position that even film students have probably never heard of? Is there a path that you followed with purpose, or did you just wake up one day and suddenly this was your job title?

LZ: [Laughs] No, but a little bit. I went to film school a long time ago. I went to NYU and when I graduated, I came to Los Angeles. I made a deal with my father: He’d pay for film school if I double-majored in business.

GL: This is an issue that comes up a lot – a lot of parents have come to believe that a career in the arts is not a “real” job. Part of it is genuine worry about their child’s future and financial stability, but it also extends to the culture at large – this idea that art is a hobby, not a career.

LZ: Right. And that is a problem. But, I have to give my father credit. I arrived in L.A. with all of the filmmaking lingo, but also a pretty good grasp of the fact that a movie is a product. It’s a more glamorous product than a bottle of ketchup, but it is a bottle of ketchup. You want it to be artistic and you want it to be something that you’re proud of – and in a film, you’ve got many artists involved – but these are artists who also understand they have to work to a time schedule and they have to deliver within a budget. It’s not like a fine artist who will take an indefinite amount of time on a piece of art – their creative process is completely within their own bubble. During the creative process on a film, no one is working in a bubble. So, there’s a certain amount of understanding that it’s a business process that can be very helpful. Now, I’m not saying that every prop maker needs to understand business. They don’t. But they do need to understand the ramifications of not delivering on time or underestimating the cost of a prop so that they either have to disappoint the production and the director or spend way more than they were authorized to spend.

GL: What was your first job out of NYU?

LZ: When I got to Los Angeles, because of my business degree, my first job was as a production secretary. I was voraciously reading every document that came across my desk. And, one day, I was making photocopies of the cost report to send to Universal. This was long before email – before email.

GL: I gathered that when you mentioned photocopies.

LZ: [Laughs] Yes, I was making a lot of Xerox copies, as we called them back then. And on this one particular cost report, the trial balance didn’t equal zero. Now, for 90 percent of the world that means absolutely nothing.

GL: Indeed. I actually just nodded and pretended to understand what you meant.

LZ: Exactly! When you’re doing accounting, you enter every expense twice – as a positive and a negative. You’re giving up money to buy something. Or, you’re selling something to get money. There’s always a plus and a minus. A trial balance is to make sure that you’ve remembered to do the plus and the minus on every transaction and the trial balance is the addition of everything and it should equal zero! If it doesn’t equal zero, then it means there’s something wrong. It doesn’t say what it is, it just shows that something is wrong. So, I went into the accountant’s office and said, “I know I really shouldn’t be reading what I’m photocopying, but I noticed that the trial balance doesn’t equal zero and I don’t think you want to send this report to Universal.

GL: Your “Xerox moment” got the attention of someone and soon you were entrusted with more responsibilities?

LZ: Well, it resulted in my becoming an accountant. My next show, I was the first assistant accountant and the show after that, I was the production accountant. I was in film production accounting for about six years and then I got promoted to production management and then to line producer. I also ran a small independent production company for about five years.

GL: Were all of these early accounting jobs for Universal?

LZ: When I was doing the production accounting, managing, line producing – that was all freelance, project by project. I produced a film for Samuel Goldwyn – as the line producer – and the producer of that film had just left. He had been president of Samuel Goldwyn and he’d left to start his own company and he hired me to be the COO and the managing producer of that company. That was the beginning of my pulling back from being directly involved with the filmmakers, and instead, overseeing and managing the bigger picture of the projects. I did that for five years and from there I went to work for the Weinsteins. I moved back to New York to become Senior Vice President of Physical Production for The Weinstein Company, doing what I do here now, at New Regency, which is overseeing our physical production. I also did some postproduction work in those early days. So, I have an understanding of postproduction too, but at these larger studios, those are two separate divisions. Having that experience is helpful for me to budget for postproduction. But, in fact, when we get to postproduction, I hand the project off to another team.

GL: When you went to film school, was it for acting, directing – what was your field of study, along with the business degree?

LZ: I had been an aspiring actress. I went to acting school in New York. And, in acting school, I discovered that I was not an actress.

GL: Did you discover that yourself, or were you told that you were not an actress?

LZ: I would say it was mutual. I was very fortunate. I went to this school called The Neighborhood Playhouse and I was there the last year that Sanford Meisner taught full time. I was there at a very fortunate moment, but Sandy made it very, very clear to me that I was not a natural.

GL: Sorry I brought it up!

LZ: [Laughs] No, no! It was a very fortunate thing that it happened when I was 21 years old, instead of later. But I was in New York, so I walked down the street to NYU and I enrolled. When I thought about filmmaking and the process and who was really in command, I decided that it was the producer. So, that’s what I studied. And the two-and-a-half years I was at NYU, I was the only person studying producing. I produced 40 films when I was there. I literally produced every single film I wanted to produce, because everyone needed a producer and there was no one else.

GL: How has that changed over the years? Do film schools now offer strong production studies and departments?

LZ: No, not that I know of. There’s the Peter Stark program. Does that even still exist? I think it does. That’s the only producing program that I know about. I really had to make my way at NYU. I had to meet with the Dean of the film school and the business school every semester to convince them of the practicality of my studies.

GL: You had to create your own degree program?

LZ: Yes.

GL: It makes sense in an odd way, if you consider that you essentially produced your own course of study in production.

LZ: [Laughs] Exactly! There are other routes to becoming a producer. Definitely, in physical production, it’s about understanding physical production. So, people graduate to it, normally, out of some path from production management to line producing – you have to have come from the role of managing a project overall. The difference is clear when you get into the studio world. It’s more of that early planning and figuring out the premise of your plan. There are places that are perfect locations, but financially not viable. And then, of course, there are places that are financially viable, but maybe not good for locations. It’s about figuring out, based on the parameters of the project – and there are no two productions that have the same parameters – what pros and cons about a particular location are more important, that’s a big part of our job. So, when we’re hiring the team for the film, we’re already telling them what’s viable because we’ve already done the research. Then, we’re not looking at the entire world to shoot a film, but have narrowed it down so that we’re comparing Atlanta and Shreveport, or Hungary and Romania. Then we decide which is the most viable.

GL: Can we talk about a recent project that was particularly challenging and why?

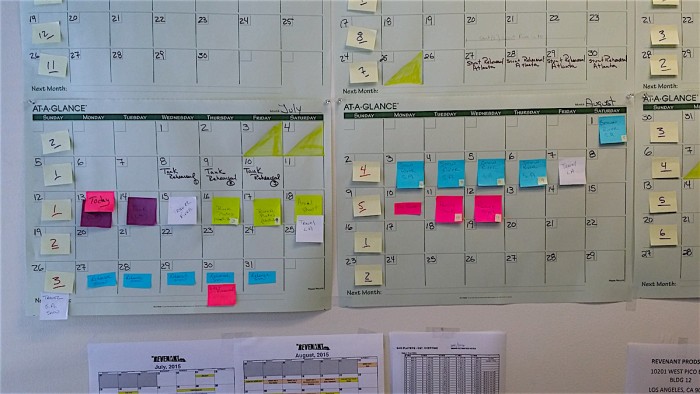

LZ: Well, the most recent and challenging – and there are not too many questions as to why it was challenging – was The Revenant. I was working on The Revenant for almost five years.

GL: Five years! Did you get your own Oscar?

LZ: No, but I get to look at our company’s Oscar [laughs]. The Revenant was a challenge because our director wanted it to be as real as possible. Just finding the locations took us about three years. It was a very difficult search, because they had to be both extraordinary and feasible. For many of the locations, the definition of “feasible” one might question [laughs]. For example, where the bear attack took place – it was in this absolutely remarkable forest. I mean, it was truly like walking into the elfin forest in Lord of the Rings. The trees were just huge. I mean, huge! And the moss, the dripping of water – it really was extraordinary. Unfortunately, it was also 28 miles up a lumbering road, for lumber trucks, through a lumber company’s land. We were actually in a national forest, but on the opposite side of this private lumbering company’s land.

GL: How was it even found?

LZ: [Sighs, stares, grins]

GL: I should probably just stop asking questions, but that’s why I’m here, after all…

LZ: [Laughs] How it was found? Well, let’s just say a location scout was a little too ambitious. That road went along a very big river and was known to wash out multiple times per year. I mean, this was in British Columbia where they get a lot of rain. Somehow, we got our huge basecamp – all of the trailers and trucks; this was a big production – all the way up this road. As a studio, we fought pretty fiercely against that location. It was extraordinary, absolutely. It looks extraordinary in the movie, but it was really high risk. We were, in fact, and this was really crazy, we were hit by a hurricane.

GL: I don’t mean to laugh, but I wasn’t expecting that.

LZ: Nor were we! This storm took the road out. You know how hurricanes are circular, right? And they often hit twice. They hit as they’re coming in – the front end of it hits and then the back end of it hits. The front end took the road out. Luckily, it was at night. We were still rehearsing; we hadn’t gotten to filming yet. But we already had everything up the mountain, along with security guys. Luckily the crew and everyone else was down at the hotel. Anyway, so the storm takes the road out and we have to get our security guys out of the location in a helicopter, in a hurricane. It was crazy. We were repairing the road and four days later, another piece of the road got taken out by the back end of the storm. What was absolutely amazing is that no equipment got lost. One trailer was waterlogged, but we actually had no serious equipment damage and the security guys were evacuated safely. And, in the end, it was fine. But, wow.

GL: The struggle you’re describing comes through in the film, in a good way. The story is a struggle. The filming was struggle. Maybe these were good “disasters.”

LZ: It was. But that was a really bad week. Actually, it wasn’t that bad for the crew, we were all at the hotel, waiting for the storm to hit. But logistically, it was really bad. The other famous story from The Revenant is we ran out of snow, so we had to figure out what to do. We had to search the planet for snow. We had to figure out what place on the planet has – as of yet – never not had snow. We ended up in Ushuaia in Tierra del Fuego, which is at the bottom of Argentina. It’s where you catch the ship to go to Antarctica. With global warming, there are very few places left in the world that always have snow every winter. Even in Alberta, we were trucking in snow to our locations. We actually had to do that in Argentina as well. So, from the filmmaker’s perspective, global warming is very real.

GL: Speaking of issues, such as global warming. You’re quite active in finding ways to curb piracy. What do you tell someone who says, “Does it really matter if I watch an illegal download of a film? Who am I hurting?”

LZ: What people don’t understand is you have to forget about the bigwigs who are making a gazillion dollars. Most of the cast, most of the film crew are earning pretty basic wages. Their hourly rate looks high, but we’re freelancers and we’re not working a lot of the time and that’s part of the reason why the hourly rates are high – it’s to help cover us during the gap when we have no income at all. So, in our union agreements, we get a profit participation from the movies. It’s tiny – as far as the general scheme of things go – but we work on lots of movies and over the course of time, over the course of your career, your residual checks get better because you are participating in more movies. But, that is a direct percentage of the receipts, right? So, if people are not paying, then I’m not getting that residual. It’s that simple.

GL: I recently had an argument with a friend who told me he watched a bootleg copy of The Witch and he was laughing about it because he saw someone’s head in the way of the screen. It was filmed inside a theater. His justification: “Well, I wasn’t going to see this movie anyway, so what does it matter?” My response: “Well, then don’t watch it. If you weren’t going to see it, then don’t see it. At all. Ever. Don’t fund the pirates!” Do you have some better counterarguments I could add to my arsenal?

LZ: Separate from my job here, I participate on the board of the CDSA, which is the Content Delivery Security Association. Many more people on the board are on the distribution and delivery side than the production side. I’m not the only one, but I’m definitely the main representative of the production side. But when you talk about piracy, it’s about finding that right price. One of the people on our board is from Microsoft and when they first went into China, their software – Office and Windows – were priced the same in China as they were here in the U.S. They had a disastrous piracy problem. They couldn’t sell it. It was pirated completely. They dropped the price to five dollars. Literally. Five dollars. We were all still paying 200 dollars around that time. Now we don’t pay for it either, but instantly they had a market. They basically dropped it to the price-point where people were fine with paying for it and actually having the real version. I think there’s a tricky thing with the film business. There are people who will just never want to pay – ever. They don’t want to pay for anything. They’ve made that life choice. I think they are a dishonorable group of people if they feel that way. But there are a group of people – and I think it’s a very large group of people – that have their own measure of what is a reasonable price. With movies, sometimes, it’s difficult, because the reasonable price for one movie might not be the reasonable price for another movie. And yet, the way we sell movies, we price them essentially at the same price. That’s a question for the industry, whether there’s any way to play with that idea.

GL: There’s 3D and IMAX.

LZ: Well, in that case, you’re not paying for the same experience. And there are those of us, like myself, that if a movie charges a premium for the 3D, I don’t go to the 3D version. It’s just not worth it to me. You also have premium theaters that are nice places to see a film and they charge extra. But I don’t know if there’s finding a price point [for movies]. Again, like your friend saying, “Well, I wasn’t going to go see the movie anyway.” And I think you have a perfectly valid point, “Then why are you watching it for free?” That’s a tricky one, because he’s saying he values The Witch less than another movie. That’s his personal choice.

GL: He was interested enough to watch it and might have become more interested over time and then finally paid for it. He pressed play, so there was some interest.

LZ: Exactly. It’s a really tough one. Particularly when accessing movies is so easy.

GL: And it’s anonymous.

LZ: It’s anonymous, yes. Although it’s becoming less anonymous. It’s so funny. They know so much about everything we do. “They,” right? [Laughs] But, I was just at a conference about this a couple of weeks ago. I was representing a really small group, but it was really about huge companies protecting the identities of their banking customers – things like that. One of the speakers was the head of security for Visa, the credit card company. He was talking about all of the data they are accumulating – what they call “big” data – they were accumulating all of this data about each of us in order to determine whether it is us or someone else using our card when we go to a store in Timbuktu.

GL: If the activity doesn’t fit the pattern…

LZ: It doesn’t fit the pattern, or it does fit the pattern. It’s like, “OK, you know enough about me to know that I – me specifically – you know that I’m shopping in the wrong store?” Why aren’t we using that to protect ourselves from pirating? The information is out there. The big data collectors are collecting the fact that you are watching bootlegged films. So the data collecting exists. I don’t know if that’s something that will come down the pike in the near future, or not. We’ll have to wait and see.

All photos courtesy of Lulu Zezza and 20th Century Fox.