Copyright is Automatic

Since 1976, under U.S. law, eligible works are immediately protected by copyright at the moment of creation. Although formally registering your copyright with the U.S. Copyright Office does provide valuable protections for professional creatives (or, in technical copyright jargon, “authors”) of works, it is not required. Instead, any eligible work has a copyright as soon as “it is fixed in a copy or phonorecord for the first time.” So, your family photographs, personal letters, drawings, etc. are automatically protected by copyright. In an era when social media sites have attempted to assert their right to exploit your personal images, videos, and other creative works for their profit, without compensating you, this automatic copyright may become more relevant.

Copyrightable Categories of Works

- Literary works

- Musical works, including any accompanying words

- Dramatic works, including any accompanying music

- Pantomimes and choreographic works

- Pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works

- Motion pictures and other audiovisual works

- Sound recordings

- Architectural works

Registration

Especially for creative professionals who intend to sell or license their work, copyright registration provides important protections that make enforcement easier for the rights holder. Learn more about copyright registration in our Creativity Toolkit.

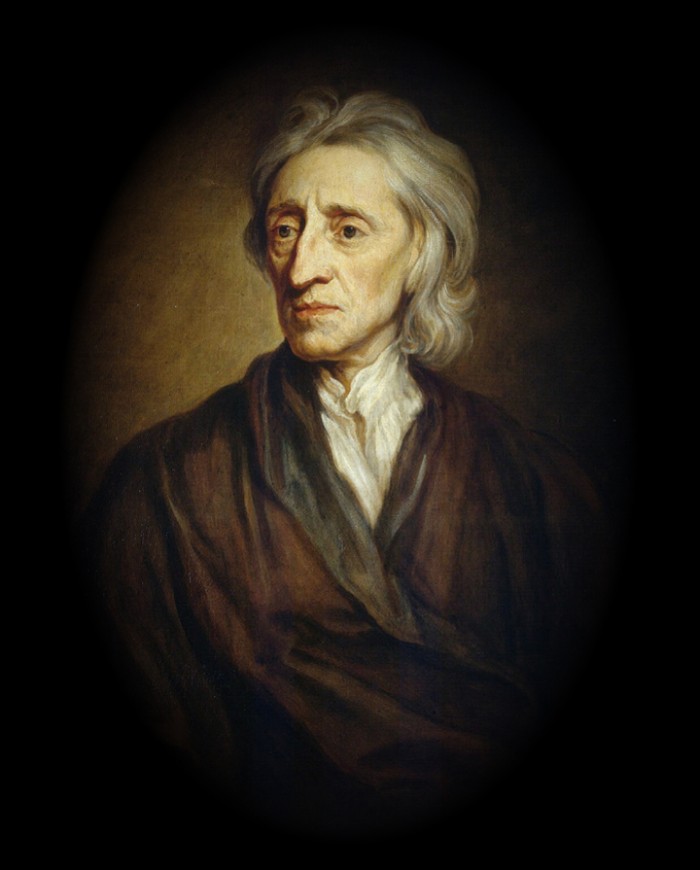

“ … Man has a property in his own person. This nobody has any right to but himself. The labor of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his.”

– John Locke, Second Treatise of Government (1689)

The idea that your work is your property dates back more than three centuries to English philosopher John Locke’s theories of government. Locke’s concept of property as including the “fruits of one’s labor” was understood by America’s founders when they wrote the intellectual property clause of the Constitution. More than just creating the foundation for copyrights and patents, this clause is an expression of the rights and the value of the individual in society. It is one reason why the US has led the world in the production of a diverse range of professional creative works.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)

Signed into law in 1998, the DMCA was intended to update portions of copyright law to reflect changes in distribution technologies, namely the internet. Although the DMCA contains several large sections, the part of the law most relevant to the creative community has become known as “Section 512.” In fact, often if someone refers to “the DMCA,” they’re very likely talking about Section 512, even though the DMCA is actually much broader.

Section 512 establishes a framework by which Online Service Providers (OSPs) receive immunity for copyright infringement committed by its users in exchange for agreeing to comply with certain practices for taking down potentially infringing work at the request of copyright owners. Section 512 also contains provisions on how non-infringing files may be restored due to error in the takedown process, in addition to several other conditions that OSPs must meet in order to remain shielded from liability.

This liability shield has become known as safe harbor.

A Basic Description of the Process

If a rights holder finds an unlicensed use of their work on a web platform, they may invoke the procedure described in Section 512 by issuing a “notification of claimed infringement” – more commonly known as a “takedown notice” – which essentially asks the OSP to remove the file. Upon receipt, the file must be removed and the user (account holder) who uploaded the file will receive a notice from the OSP informing him that the rights holder has filed a takedown notice.

If the user believes the notice was submitted in error, he or she may file a counter-notice, which requires the OSP to restore the file within 10-14 days. Unless the rights holder notifies the OSP within 10 days that they have begun legal proceedings against the user for copyright infringement, the file will remain online. The rights holder has no further recourse under the DMCA.

Challenges with Section 512

Challenges with Section 512

When the DMCA was written, we had a very different internet. Congress could not have anticipated the volume of infringement that occurs today, which totals in the tens of millions each month. Congress intended for the DMCA to serve as a catalyst for rights holders and OSPs to collaborate in the development of “standard technical measures” in order to mitigate mass infringement. In general, this collaboration has not happened.

The result is a system where rights owners must continually patrol the internet, identifying infringements one at a time, and issuing takedown notices. Since each instance of infringement requires its own notice, rights owners end up issuing thousands of notices only to see their work uploaded again and again. It’s become known colloquially as the “Whack-a-Mole” problem, and it has become one of the biggest challenges for creatives trying to enforce their rights on the internet.

To combat this problem, many copyright owners have advocated for a “takedown-staydown” regime, which would require OSPs to keep infringing content offline once the copyright owner has issued a takedown notice for that particular piece of work.

Opponents to such a regime fear that abusive notice-sending practices might result in an internet where rights owners could effectively limit free speech by issuing erroneous takedown notices or notices for uses that arguably fall within the boundaries of fair use. Because the OSPs would then be required to keep the content offline, opponents assert that such a rule would stifle free speech.

Although abuses of DMCA do occur, the vast majority of notices sent to the major OSPs are valid. If you’re the content owner and find someone who uploaded a full-length episode of your television show or movie, you will file a takedown notice. If that uploader then issues a counter-notice there is nothing more that the content owner can do except pursue expensive federal litigation. As a result, the DMCA has proven ineffective for many small and independent rights holders.

On the other side, if an uploader believes content was removed in error – e.g., a critical review of a television show or movie that makes extensive use of clips that would likely constitute fair use – he or she can file a counter-notice and have the file restored.

A 21st Century DMCA

Both copyright owners and OSPs have legitimate reasons to be concerned with aspects of the DMCA as it stands today. The law was written nearly 20 years ago, at the dawn of a digital era that has evolved dramatically in the years since it was enacted. It’s no secret that technology moves quickly and almost always outpaces the legislative process. As we move forward, cooperation among copyright owners and Online Service Providers will be essential.

Challenges with Section 512

Challenges with Section 512